|

What is meat?

Every time you step up to your grill or into your kitchen, you begin a science experiment. As meat is heated, it undergoes physical and chemical changes, and as scientific as these processes are, they are also magical. A basic understanding can help you cook juicier chicken breasts and more tender steaks. This article is an overview and the links within take you to articles that explain the concepts in greater detail.

"My foe, my enemy, is an animal. In order to conquer him I have to think like an animal and, whenever possible, to look like one. I've got to get inside this dude's pelt."Carl Spackler (Bill Murray) in Caddyshack, 1980

Meat is cut from the muscles of mammals and birds. For some reason, fish muscle is not considered meat by some people, but it should be.

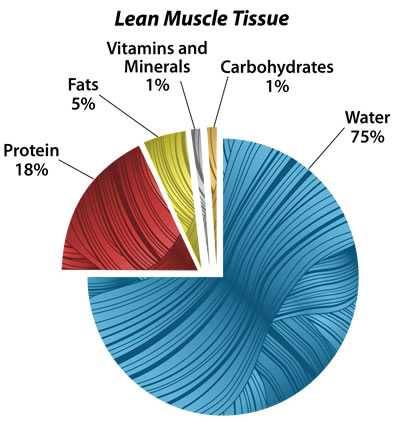

On average, lean muscle tissue typically breaks down like this: Water (about 75%), protein (18%), fats (5%), carbohydrates, salt, vitamins, sugars, and minerals (2%). Here are some specifics.

| Animal |

Water

|

Protein

|

Fats

|

Other

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beef | 72% | 21% | 6% | 1% |

| Pork | 69 | 20 | 10 | 1 |

| Chicken | 73 | 21 | 5 | 1 |

| Lamb | 73 | 20 | 5 | 2 |

| Cod | 81 | 17 | 1 | 1 |

| Salmon | 64 | 21 | 14 | 1 |

Different cuts from within an animal can differ significantly. As shown above, the average water content of pork is 69%. Pork rib meat, however, is more like 65% water, 18% protein, 15% fat, and 2% carbohydrates, salt, vitamins, sugars, and minerals. Even so, 65% is a pretty high percentage of water. With that much water in the meat, any loss you might have from stabbing it with a thermometer or an occasional stab with a fork is minor, so don't let the snobs tell you that you are going to ruin the meat if you use a thermometer to check its temp or a fork to turn it. To illustrate: if you have an 8-ounce filet mignon, 6 ounces is water. Stab it and a few drops leak out from the puncture site, an insignificant part of the 6 ounces. Meat is not a balloon that goes phffffft and deflates when you poke it with a thermometer or fork

Muscle cells

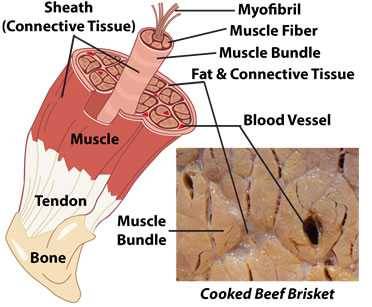

Muscle cells are more frequently called muscle fibers because they are shaped like tubes. Muscle fibers bundled together are called sheaths, and sheaths bundled together are called muscle or meat.

The fibers, about the thickness of a human hair, contain several types of protein, among them myosin and actin which bind up water and act like living motors by contracting and relaxing on command. As animal ages, grows, and exercises, its muscle fibers get thicker and tougher. And muscles like shoulders and legs get thicker and tougher than the smaller, more tender muscles call "tenderloins" that run along the animal's spine.

Myoglobin is another important protein in muscle fibers. Myoglobin receives oxygen and iron from hemoglobin in the blood, the fuel necessary for muscles to function. Myosin and actin are not water-soluble, but myoglobin is water-soluble, and myoglobin dissolved in water is the pink liquid we see seeping out from a package of raw meat or spilling onto the plate when we cut into cooked meat. When warmed, those meat juices lose their red color, become pink, and eventually tan or gray. Fibers also contain other proteins: enzymes. Enzymes play an important role in aging meat.

Connective tissue

Connective tissue is most obvious in the form of tendons that connect muscles to bones. It is also visible as the thin shiny sheathing that wraps around muscles called "silverskin" and in ligaments that connect muscles to other muscles. These tougher, chewier, rubber band-like connective tissues are mostly protein and appropriately named elastin. We call them gristle and they shrink when heated and become unchewable. As with muscle fibers, connective tissues thicken and toughen as an animal exercises and ages.

A softer connective tissue called collagen is scattered throughout the muscle, often surrounding fibers and sheaths holding them together. When you cook, collagen melts and turns to a rich liquid called gelatin, similar to the stuff Jell-O is made from. Cooked muscle fibers, no longer bound together by collagen, are now uniformly coated with a soft, gelatinous lubricant. This smooth and sensual substance enrobes meat in a wonderfully silken texture and adds moisture. And yes, this is pretty much the same stuff the Hollywood wives have injected into their faces to get rid of wrinkles.

Lean meats like beef or pork loin and tenderloin, as well as most chicken and turkey, don't have much collagen. When cooking tough cuts of meat with lots of connective tissue, like ribs, brisket, and shoulder, it is important to liquefy the meat's connective tissue into gelatin: that's what makes these tough meats taste tender. This takes time. That's why these cuts are often cooked low and slow. Muscle fibers start seizing up around 125°F to 140°F if heated quickly. But when heated slowly, the rubber band-like connective tissues have time to relax and do not squeeze tightly. In general, it is best to cook all meats at about 225°F. Slow roasting does wonders for meat. The AmazingRibs.com science advisor Prof. Greg Blonder says "Think of silly putty. Pressed hard and quickly, it acts like a rigid solid. Pressed slowly, it flows." When heated slowly, the muscle fibers, instead of wringing out moisture, relax and simply let water linger inside until evaporation drives it out.

After it melts, as it chills, gelatin can solidify into that jiggly stuff which, with a little filtering, can then be called aspic and served at bridge clubs. Here's a pot of the stuff made simply by boiling a couple of chicken carcasses in water after I ate the meat, discarded the bones, and chilled the liquid. The white is fat, most of which I have removed, and the tan is jiggly gelatin.

Fats

Fats (lipids) and oxygen are the main fuels that power muscles. Fats are packed with calories, which are potential energy released when the chemical bonds are broken. From a culinary standpoint, fat comes in three types (see the photo at the top of the page):

- Subcutaneous fats are the thick hard layers beneath the skin.

- Intermuscular fats are layers between muscle groups.

- Intramuscular fats woven amongst the muscle fibers and sheaths improve meat's moisture, texture, and flavor when cooked. These threads of intramuscular fat are called marbling because they have a striated look similar to marble.

Large fat deposits can also be found around organs, especially kidneys. On hogs, the best fat of this type, at least from a culinary standpoint, especially if you make pie crusts, is called leaf lard, and it comes from around the kidneys.

Fats are crucial to meat texture. Waxy when cold, fats start to melt around 130°F to 140°F, lubricating muscle fibers just as they are getting tougher and drier from the heat. Fat does not evaporate like water when you are cooking.

Fat also provides much of the flavor in the meat. It absorbs and stores many of the aromatic compounds in the animal's food. As the animal ages, those flavor compounds build up and get more noticeable. After the animal is slaughtered, the fat can turn rancid if stored too warm, too long, or in contact with oxygen. So we have a tradeoff. The muscle fibers and connective tissues get tougher as the animal ages and exercises, while the fat accumulates and builds flavor.

Fats, especially animal fats, are the subject of great debate among scientists, doctors, dietitians, and health faddists. For many years, animal fats were thought to be dangerous and avoided. It is now thought that fats, even animal fats, contain many beneficial components, and current science argues that, in moderation, they are essential for health. A great deal of interesting research on the subject is going on as I type this. A great deal of research is contradictory. Read more about what I have learned about food and health in this article.

Fluids

Most of the liquid in meat is water. The reddish color in meat and its juices is not caused by blood. It is the protein myoglobin dissolved in water. Myoglobin is found only in muscle, not in the bloodstream. The blood is pretty much all drained out in the slaughterhouse. If the stuff on your plate when you sliced steak was blood, it would be much darker, like human blood, and it would coagulate, like human blood. If the fluids were blood, then pork and chicken would be dark red. It's mostly just water, so let's stop grossing out our kids, and just call it juice. OK? Every time you call meat juices blood, a bell rings and a teenager becomes a vegan. Click here to Tweet this bit of wisdom

When animals are alive, the pH of the muscle fibers is about 6.8 on a scale of 14. The lower the number, the higher the acidity. The higher the number, the more alkalinity and less acidic. At 6.8, living muscle is just about neutral. When the animal dies, the pH declines to about 5.5, making it acidic. At this pH, muscle fibers form bunches and squeeze out the juice, called a purge, and that is the juice you see in packages of meat that is absorbed by the diapers they put under the meat.

Slow-twitch vs. fast twitch muscles

Muscle fibers need fat and oxygen for fuel. Fat comes from fatty acids in the animal's blood that were created by the digestion of its food. Oxygen is carried by the protein hemoglobin in the bloodstream, and it hands the oxygen to myoglobin within the muscles.

In general, the more exercise a muscle gets, the tougher it is, and the more oxygen-laden myoglobin it needs. Myoglobin turns meat darker and makes it more flavorful. Dark meats, like chicken thighs, are made of "slow-twitch" muscles that have evolved to endure slow, steady movement, and they are loaded with juicy myoglobin. White meats, like chicken breasts, are mostly "fast-twitch" muscles, which are better suited to brief bursts of energy, and they have less myoglobin. Dark meats also have more fat for energy.

When cooked, the slow-twitch muscles in dark meat have more moisture and fat and are more flavorful than white meat. White meats contain less moisture and fat, and they dry out more easily when cooked. The legs and thighs of chickens and turkeys are good examples. These animals get more exercise standing and walking than flying, so the legs and thighs have lots of slow-twitch muscles, more pigment, more juice, more fat, and more flavor. They are also slightly more forgiving when cooked. Modern chickens and turkeys have been bred for large breasts because white meat is more popular in this country (and I for one, can't understand why). I'll take tough and flavorful over tender and mild any day.

[Like what you’re reading? Click here to get Smoke Signals, our monthly email that tells you about new articles, science, recipes, product reviews, and more. Be Amazing!]

Ducks and geese excel at flying and swimming, and they get more exercise than chickens and turkeys, so these birds have more dark meat. Duck breasts are deep purple, almost the same color as lamb or beef.

When the conventional wisdom was that dietary fat could cause heart and arterial problems, domestic pigs were bred to have less intramuscular fat. The modern pig does not get much exercise due to its transmogrification into "the other white meat." In recent years, research has questioned the relationship between dietary fat and health, and many experts extol fat's benefits.

Beef is all pretty much the same color, but slow-twitch muscles like flank steak have bigger, richer flavor than some of the lesser-used muscles like tenderloin.

Fish live in a practically weightless environment, so their muscles are very different. Fish muscles have very little connective tissue, and that's one reason why fish never gets as tough as pork when cooked. But fish can dry out because there is not much collagen to moisturize the muscle fibers. The color and texture of fish vary depending on the life it leads. Small fish that swim with quick darting motions have mostly fast-twitch muscles and white meat, while flounder, which lives on the seafloor, has delicate flaky flesh. Torpedos like tuna and swordfish swim long distances with slow steady tail movements, so they have had firmer, darker, sometimes even red flesh. For these reasons and others, fish can spoil within days of being caught, while red meats keep much longer.

Brown is beautiful, black is bad

As meat cooks, the most magical transformation that occurs is the Maillard reaction. It is named for a French scientist who discovered the phenomenon in the early 1900s. The surface turns brown and crunchy and gets ambrosial in the aroma. Who doesn't love the crispy exterior of a slice of roast beef, the browned crust on freshly baked bread, or the crackling surface of a roasted marshmallow? We don't think twice about it, but that brown color on the surface is the mark of hundreds of compounds created when heat, especially heat above 300°F, starts changing the shape and chemical structure of the amino acids, carbohydrates, and sugars on the surface of the meat. Click here to learn more about the Maillard reaction and caramelization.

What you don't want is black meat. Let it go too far and it turns to carbon. Carbonized meat may be unhealthy.

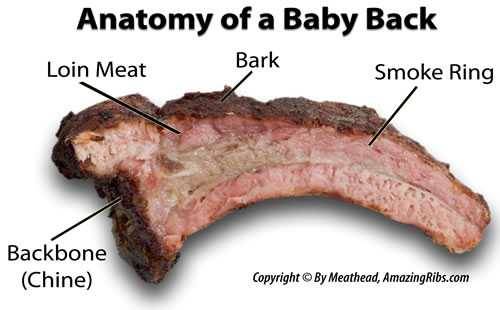

Pretty in pink

There's another color you may notice in cooked meat: pink. Many smoked types of meat turn bright pink just under the surface. Some people think that the pink color means that meat is raw, but not in this case. If the meat were undercooked, the pink would be in the center, not just below the surface. Pink meat near the surface is a common phenomenon called the smoke ring and it is caused by gases in smoke preserving the color of myoglobin. Some people think the smoke ring improves taste. That's a myth too. Click here to read more about the smoke ring and what causes it.

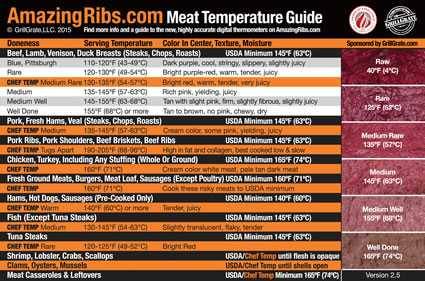

Cook with a thermometer, not a clock

Different cuts of meat vary significantly in tenderness, fat content, and collagen content. Some are best cooked hot and fast, some better cooked low and slow, and some must be cooked with a combination of hot and slow to reach their optimal taste and texture. Click here to read an article on the subject of cooking temps.

This is why cooking times are guesstimates at best. Think about the absurdity of a recipe that says, "cook the steak for six minutes on the first side and then four minutes on the second side." How long it takes to cook depends on how hot the air and the cooking surface are, how thick the meat is, and your target temp. Depending on the grill, cooking steaks could take twice as long or half as long. Thick steaks take more time, and if you want them rare, they'll take less time than in if you want them well done. Click here for more on cooking times and what controls them.

You cannot tell if the meat is safe or cooked to the proper temp by looking at it. When you cut into the meat to look at it, it can change in a few minutes after it has been exposed to oxygen. Compounds in marinades and brines can impact color. Sometimes vegetables in the grill can produce gases that alter meat color. It has long been thought that when chicken juices run clear the meat is safe, but modern chicken farming has changed that. Use a thermometer. Click here to read how we bust the myth of clear chicken juices.

The truth is, meat can go from succulent to sucky in just a few minutes. The only way to be sure about doneness is to use a digital thermometer. Overcook meat and you've wasted your money. Undercook it, and you could give someone a tummy ache or much worse. That is why you ALWAYS cook with a thermometer, not a clock. This is the 21st century. The digital age. Stop using 19th-century technology. Ditch your dial telephone and your dial thermometer.

And while you are at it, get a digital oven thermometer. The cheap dial thermometer that came on your grill or smoker is probably off by 25 to 50°F like the one above. I have seen them off by 100°F!

As the internal temp of meat climbs, more water gets squeezed out, and the meat becomes drier. In general, most meats are juiciest when cooked to medium-rare, 130 to 135°F internal temperature.

But that's not hot enough for safety in some meats. Ground meats and poultry are health risks at those temps. Ground meats need to be cooked to 160°F, and poultry needs to go to 165°F to kill pathogenic bacteria. But there's more to the story than that. You can actually serve these meats at lower temps if you know the rules. Read my article on meat temperatures.

Meats with a lot of connective tissue such as beef and pork ribs, pork shoulder, and beef brisket, are too tough at these lower temps. They need to go up to 200 to 205°F in order to gelatinize collagens and melt fats. That's well past well done, and yes, water is lost, but the gelatin and melted fats lube the meat and make it taste tender and juicy.

Be aware that if you let the meat sit around after you remove it from the heat, the heat built up in the outer layers will push down to the center and overcook the meat, a process called carryover cooking. The good news is that resting meat is probably not necessary, despite what all the TV chefs say. For more about ideal serving temps, read my detailed Food Temperature Guide, which has a handy printout for your fridge.

What happens when you cook?

Here's a general guide to temperatures organized from cold to hot. The meat temps shown here are approximate because other variables come into play such as the age of the animal, acidity, salt content, type of heat, humidity, etc. This info has been gathered from multiple sources, including meat science research papers, textbooks, and Harold McGee's important book, On Food And Cooking. Click here for a complete guide to target cooking temperatures.

0°F (-18°C). Ideal freezer temperature.

25°F (-4°C). Meat freezes. The meat starts to freeze at a lower temperature than water because the water in meat is combined with proteins. Water expands as it freezes and sharp-edged crystals form that can rupture cell walls, creating "purge" when the meat is thawed, which is a spilling of liquid, mostly the pink fluid protein called myoglobin. Faster freezing makes smaller crystals, resulting in less purge.

32°F (0°C). Water freezes.

34-39°F (1-4°C). Ideal refrigerator temperature. Water is not frozen, and microbial growth is minimized. You do have a good refrigerator thermometer, don't you?

41-135°F (5-57°C). The "USDA Danger Zone," in which many pathogenic bacteria grow, sometimes doubling in number in as little as 20 minutes. According to the USDA, cold foods must be stored below 41°F (5°C), and hot foods above 135°F (57°C). That's why we don't leave meats sitting around to come to room temp.

60°F (15°C). When chilling cooked meat, liquid gelatin forms a solid gel called aspic. Gelatin happens when connective tissues that wrap muscle fibers and connect them to bones, called collagen, melt. Yep, it's the same stuff they inject under your skin to hide wrinkles.

95-130°F (35-54°C). Animal fats start to soften and melt.

114°F (46°C). Myofibrillar proteins begin to gel, changing meat texture.

120°F (49°C). Myosin, a protein involved in muscle contraction within fibers, begins to lose its natural structure. It unwinds or unfolds, a process called denaturing. It starts to clump, gets milky, and begins firming up the muscle fibers. Purple meats, called "rare," start turning red. Fish begins to flake, and parasites begin to die.

130°F (54°C). Many pathogenic bacteria begin to die, slowly at first, but as the temp rises, they croak more rapidly. At this temp, it takes more than two hours to pasteurize meat. At 165°F (74°C), it takes just seconds.

130-135°F (54-57°C). Medium rare. Most mammal meats are at optimum tenderness, flavor, juiciness. If you eat your meat well-done, you need to snap out of it.

130-140°F (54-60°C). Fats begin to liquefy, a process called rendering. This is a slow process and can take hours if the meat is held at this temp.

140°F (60°C). Connective tissues called collagens begin to contract and squeeze out pink juice from within muscle fibers into the spaces between the fibers and out to the surface. Meat begins to get dry. Myoglobin, the pink protein liquid within muscle cells, denatures rapidly and red or pink juices begin to turn clear or tan and bead up on the surface. It is not blood!

150°F (66°C). Actin, another protein important to muscle contraction in live animals, begins to denature, making meat tougher and drier still.

150-165°F (66-74°C). This is "the stall zone," in which large cuts such as pork butt and beef brisket seem to get stuck for hours when cooked at low temperatures like 225°F (107°C). In this range, moisture evaporates and cools the meat like sweat on an athlete. Inexperienced cooks panic. Eventually, temps start rising again. Whew!

155°F (68°C). Known as "well done," meats are overcooked at this internal temperature. Much moisture has been squeezed out, and fibers have become tough. Bacteria are killed in less than 30 seconds, but spores can survive too much higher temps.

160-165°F (71-74°C). The "instant kill zone." Normal cooking temps kill microbes on the outside of meats rapidly, so solid muscle meats are not likely dangerous since contamination is almost always on the surface. But ground meats and poultry often have bad guys beyond the surface, so you must cook these meats beyond the instant kill zone. That's why the recommended internal temp for ground meats is 160°F (71°C) and for poultry is 165°F (74°C). When you reheat foods, you should take them up to 165°F 75°C).

160-205°F (71-96°C). Tough collagens melt and form luscious gelatin. The process can take hours, so low and slow cooking creates the most gelatin. Dehydrated muscle fibers begin to fall apart and release from the bones. Meat becomes easy to shred. Even though the fibers have lost a lot of water, melted collagen and fat make the meat succulent.

212°F (100°C). Water boils at sea level. The boiling point declines about 2°F for every 1000' above sea level.

225°F (107°C). Ideal air temperature for "low & slow" cooking of meats high in connective tissue. It is high enough so the water evaporates from the surface to help form the desired crust called "bark," but low enough to get the most out of enzymes, collagen melting, and fat rendering.

230-234°F (110-112°C). Table sugar melts and pulls into a thread but will not form a ball (thread stage).

300°F (149°C). Butter starts to smoke.

310°F (154°C). The Maillard reaction accelerates surface browning, which is caused by chemical changes in proteins and sugars and results in thousands of delicious new molecules. The Maillard reaction begins at lower temps but really takes off at 310°F (154°C).

320°F (160°C). Table sugar liquefies, starts to caramelize, turns light amber in color (clear liquid stage).

325°F (163°C). Ideal air temperature for cooking chicken and turkey so skin browns and fat renders.

350°F (177°C). Table sugar and brown sugar begin to burn (burnt sugar stage).

361°F (183°C). Some animal fats begin to smoke.

375°F (191°C). Extra virgin olive oil begins to smoke.

400°F (204°C). Canola oil begins to smoke.

425°F (218°C). Teflon thermometer cables can begin to melt.

440°F (227°C). Inexpensive olive oil begins to smoke.

450°F (232°C). Peanut oil begins to smoke.

450°F (232°C). Some nonstick surfaces begin to emit toxic gases.

570-750°F (299-399°C). Primary combustion temperature of hardwood, wherein it smolders and releases large quantities of unburned gases, including microscopic particles called smoke.

600-700°F (316-371°C). Flashpoint or fire point, the temperature at which smoke from burning fat can burst into flame. Never use water to extinguish burning fat. Smothering it works better.

1110°F (599°C). Secondary combustion of wood when gases, cellulose, and lignin burn rapidly.

What causes properly cooked pork and poultry to be pink, even if it is not smoked?

Several factors: Gases in the atmosphere of an oven, particularly carbon monoxide, can react with myoglobin in meat and turn it pink, especially on the outer edges. These gases occur in all ovens, especially those that heat by combustion such as gas, charcoal, or wood. They are also present in electric ovens but to a much lesser degree. When grilling or smoking, there are more of these gases. They more easily penetrate the thinner skin and fat layers of younger animals, so the age of the animal is also a factor.

Also, meats with high levels of naturally occurring compounds such as myoglobin are more likely to turn pink. Nitrites in meat can also cause pinking. Nitrites are converted from nitrates in feed and water by microorganisms within the animal. Nitrates naturally occur in many leafy vegetables and can transfer to the meat during cooking, say, from a rub or braise. In fact, grocery store meat trays are occasionally packed with carbon monoxide or nitrogen to keep the meat in the pink.

Why is raw red meat sometimes bright red on the outside and dull gray on the inside?

Fresh cut or ground beef is purplish-red in color. Oxygen reacts with the pigments in red meat to form the bright red color in the grocery store. The interior of the meat may be gray or brown because oxygen has not penetrated into the muscle. This is normal. If, however, all the meat in the package has turned gray or brown, it may be spoiling.

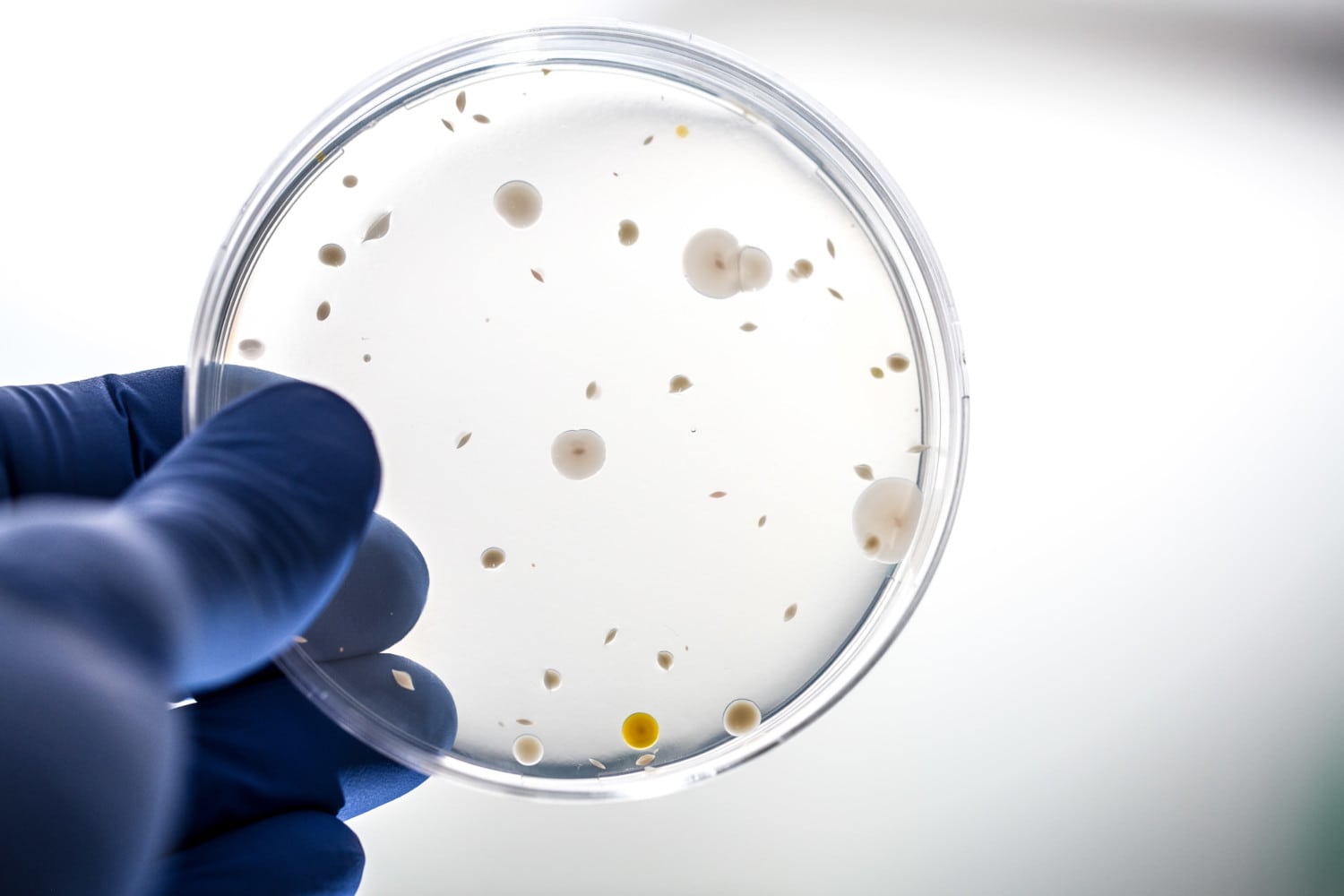

What is spoilage?

There are two types. Oxidation is caused by compounds in meat combining with oxygen and changing the meat's smell, flavor, and color. Badly oxidized meat is called rancid. But oxidized meat is usually not dangerous. The other type of spoilage is bacterial or viral spoilage, and it is very dangerous. There are several commonly occurring bacteria in food that can spoil it, such as are Bacillus cereus, Campylobacter jejuni, Clostridium botulinum, Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella, Shigella, Staphylococcus aureus, and STECs (Shiga toxin-producing E-coli). Some of these bacteria will merely have you kneeling before the porcelain god, but others can maim or kill you. You can begin killing bacteria by cooking food to a safe temperature of 131°F or higher. At 165°F, bacteria are killed instantly. At 131°F, it can take hours. For more on bacterial kill temps, click here and scroll down.

Why is meat in my fridge is turning brown?

At first, oxygen reacts with pigments to turn meat red. After a while, the meat starts to oxidize, which turns it brown, the same way an apple or potato turns brown.

Why does my meat shine like a rainbow?

It is simply a fluke of lighting that strikes the surface just the right way when the surface has been cut on a certain angle. Strictly refraction, not bacteria or an oil slick.

Why is my meat green?

Bad bacteria. Throw it out.

Why are there are dry white spots on my meat from the freezer?

That's freezer burn. It's like frostbite. The meat has probably been in the freezer too long and/or it was not wrapped tight. It is still safe, but the burned parts will probably be dry and bland. Trim it off and cook it, but don't serve it to Mom or the boss.

My meat smells funny, what should I do?

Sometimes meat will smell a bit odd when you take it out of a vacuum-sealed plastic bag, but the smell should dissipate within a few minutes. If it still smells funny, then chances are it is funny. Throw it out. Remember: when in doubt, throw it out!

What are those boogers coming out of my burgers and my salmon?

In salmon, boogers consist of another group of proteins dissolved in water called albumin. The albumin is pushed to the surface by shrinkage caused by heat. Brining helps minimize it, but not always. Salmon boogers can usually be wiped off with a paper towel or a brush. Another good technique is to paint the surface with a simple wash of sweet wine, mirin, or a glaze.