Smoke is the essence of barbecue. It is what differentiates barbecue from other types of cooking.

"'When a lovely flame dies, Smoke gets in your eyes.' Song 'Smoke Gets In Your Eyes'"by Jerome Kern and Otto Harbach, performed by The Platters

Originally all barbecue and grilling was done with logs of dried hardwood as the sole fuel source. Heat cooked the meat, and smoke from the wood and from dripping juices imparted a distinctive seductive scent that is the essence of barbecue. But it is difficult to control the heat and flavor when cooking with logs, so today, only a few expert pitmasters outfitted with special rigs cook with logs only.

Today, most grills and smokers use charcoal or gas to produce the heat, although a few use wood pellets or electricity. They get flavor and aroma from the addition of wood in the form of wood chips, chunks, bisquettes, pellets, logs, or sawdust. When heated, they make smoke. Smoke can also come from meat drippings, which are laden with fat, protein, spices, and even sugars from sauces. Adventurous cooks can also get smoke from dried herbs, tea, and even hay. But not all smoke is created equal.

Smoke is a combination of tiny particles that we can see in an aerosol mixed with water vapor and a complex cocktail of gases. The exact mixture is crucial and it can add elegant vanilla and brown spice notes or coarse bitter ash tray taint.

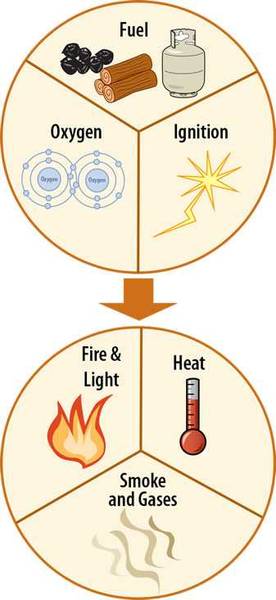

Cookers that get heat from logs, charcoal, gas, pellets, and electricity each produce noticeably different flavors because each fuel produces a unique combination of combustion byproducts.

Combustion, as it applies to barbecue and grilling, is a sequence of chemical reactions between oxygen and another fuel that are ignited producing a change in the chemistry of both, creating heat, light, and smoke with its blend of particles, water vapor, and gases.

This video gives a good overview of this article.

Burning wood

Hardwoods, deciduous trees which include fruit and nut woods, have compact cell structures, and they are the best woods for cooking. Softwoods, like pine, fir, spruce, redwood, hemlock, and cypress, are all evergreen, coniferous trees, and they have more air, more pungent sap, and they burn fast. They are not recommended for cooking. We'll talk more about different wood types below.

Fresh cut hardwood has a lot of water in it, up to 50% by weight, it produces a lot of steam and off flavors during combustion, and it takes up to 45% more energy than charcoal or gas to dry it out, so most wood for cooking is hardwood that has been air dried.

Dried hardwood is rarely totally dry, perhaps 5% water. Of the remaining 95%, about 40% is cellulose, about 40% hemicelluloses, 19% lignin, and 1% minerals. Actual numbers will vary depending on the wood species, subspecies, age, soil, and climate.

Cellulose and hemicelluloses are large molecules made of carbohydrates and sugars. Lignin is another complex compound that gives wood strength, and it is found mostly in cell walls.Wood also contains oxygen, nitrogen, carbon, and hydrogen among many other molecules. The minerals in wood include, potassium, sulfur, sodium, chlorine, and heavy metals. Although there are only trace amounts, these minerals can significantly impact the aroma and smoke flavor.

According to The Forest Encyclopedia, smoke flavor is influenced more by the climate and soil in which they are grown than the species of wood. This is very important to note, especially when you are caught up in the game of deciding which wood to use for flavor. This means that the differences between hickory grown in Arkansas and hickory grown in New York may be greater than the differences between hickory and pecan grown side by side. More on this below.

When burned thoroughly in a lab, wood produces about 8,600 BTUs of heat per pound, about half of the mass is converted to carbon dioxide and about half to water vapor. In the real world of a grill or smoker, wood is never burned thoroughly.

Wood has a lot of airspace in it and is a good insulator. That's why you can set one end of a stick on fire and hold the other end. It is also why wood burns unevenly with different parts at different temperatures.

Dr. Blonder explains that during combustion wood goes through four stages. When it is really going good, all four stages can be happening at once.

Stage 1 - Dehydration (up to about 500°F). In this stage wood must be heated from an external source like a match, kindling, rolled up newspaper, or (horrors) lighter fluid. The wood drys out the rest of the way, water steams and evaporates, and some gases like carbon dioxide are given off, but there is no flame or heat produced.

Stage 2 - Gassification and pyrolysis (500 to 700°F). Here's where combustion begins. The compounds in wood begin to change, and some come off as flamable gases, some form oily liquids and tars. The gases will burn if you give it an ignition source like a flame or spark, but they will not ignite on their own. Let's call the combustion point 575°F on average for the sake of discussion.

Stage 3 - Burning bush (700-1,000°F). An apt term coined by Dr. Blonder to describe the phase most important to cooks. Flame appears and more gases emerge, among them nitric oxide (NO) which is essential for formation of the smoke ring in meat. In the sweet spot of about 650 to 750°F, the best aromatic compounds for cooking come off, among them guaiacol and syringol, which are primarily responsible for the aromas we call smoke. Some are ethereal and dissipate, and that's why barbecue doesn't taste the same after it has been reheated. As the temp rises above 750°F, acrid, bitter, and possibly hazardous compounds are formed.

During the burning bush stage, heat creates gases that rise from the fuel creating something like a gas bubble, but the wood itself is not consumed. The bubble is surrounded by air that is about 20% oxygen. If there is any source the gas bursts into flame as the gases and oxygen combine. If all the gases are able to combine with the oxygen, a blue flame is visible. This never happens with wood or charcoal so the flame glows yellow or orange. If unburned gases escape, the bubble cools and creates smoke. Charcoal and wood fires are inefficient and so their flames are orange, yellow, and red.

Stage 4 - Charcoal formation (above 1,000°F). Most of the organic compounds have burned off leaving behind pure carbon, or char, which burns with little smoke.

Burning propane and natural gas

A gas grill has a venturi, a valve that blends the gas and oxygen like a carburetor. When there is too little oxygen some of the fuel is unburned and sooty. The soot glows yellow and orange, like an ember. When properly blended all the fuel is completely burned and the flame is nearly blue. Click here to read more about gas grills and smokers and how they work.

When propane or natural gas combine with oxygen and they are ignited, they produce water vapor, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, and not much else. Wood and drippings are needed for flavor.

Burning charcoal

Charcoal is almost pure carbon made from wood that has been preburned in an oven with very little oxygen. When burned in a grill or smoker, charcoal, like wood, it burns hotter than wood and produces a lot of combustion byproducts, although fewer than does wood. For a detailed explanation of how it is made and how it works, read my article on the Science of Charcoal.

Electricity

Electric cookers use a glowing metal coil for heat, so there is no flame, and no combustion gases. Even if you put wood chips on an electric coil, the flavor of the smoke is vastly different, and to many tasters, inferior for most foods because it lacks the complexity that the combustion gases from wood or charcoal produce. Even though propane or natural gas don't produce a lot of combustion gases, they burn at a hotter temperature producing better smoke.

What is smoke?

Smoke includes as many as 100 compounds in the form of microscopic solids including char, creosote, ash, and phenols, as well as combustion gases that include carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, nitric oxide, syringol, and liquids such as water vapor and syringol, an oil.

Trace amounts syringol are responsible for much of the smoke aroma we love and trace amounts of guiacol are responsible for much of the taste of smoke. The composition of smoke depends a great deal on composition of the wood, the temperature of combustion, humidity, and the amount of oxygen available.

If the wood does not get enough oxygen it can still undergo pyrolysis and gassification, but not burning bush. It will not burst into flame, it will smolder, and smoldering wood produces lots of smoke and a different flavor than burning wood. Why would it not get enough oxygen? If the intake vents and chimney are not open wide enough. Click here to learn more about controlling vents and chimneys. Getting enough air can be a problem in kamado type smokers that are so well insulated and retain so much heat that we often have to choke off airflow to keep it from running too hot.

Wood also plays a role in the color of the meat and the formation of the crust on the meat, also called the bark. Below are two slabs of ribs with the same spice rub but no sauce. The one on the left was cooked on a charcoal smoker and the one on right was cooked on a gas smoker. You can see and taste the difference. They were both excellent, but different. The one on the right had a bit of a bacon or ham undertone, typical of gas smokers.

Blue smoke for long cooks

Smoke from wood or charcoal for cooking can range from bluish, to white, to gray, to yellow, brown, and even black. The most desirable smoke is almost invisible with a pale blue tint. You can see it below. Blue smoke is the holy grail of low and slow pitmasters, especially for long cooks.

Dr. Blonder explains that the color depends on the particle size and how it scatters and reflects light to our eyes. Pale blue smoke particles are the smallest, less than a micron in size, about the size of the wavelength of light. Just because you can't see it, doesn't mean it's not there. Pure white smoke consists of larger particles, a few microns in size, and they scatter all wavelengths in all directions. Gray and black smoke contains particles large enough to actually absorb some of the light and colors.

Black and gray smoke happen when the fire is starving for oxygen, and they can make bitter, sooty food tasting like an ash tray. Billowing white smoke is common when you just start the fire, and when the fuel needs lots of oxygen as it goes through stages 1 (dehydration) and 2 (gassification). If it doesn't get enough and if the fuel is not emitting gases for stage 3 (burning bush combustion), the fuel smolders and produces white smoke. For short cooks of thin meats, you might just want the heavier, more intense white smoke, and we'll discuss that below. Here are some tips on how to get blue smoke for long cooks.

Get your smoke from wood. Don't worry if your wood bursts into flame. A lot of beginners fret over their burning wood and want it to smolder and belch smoke. You'll use more wood if you let it burn, and you'll have to struggle a bit to maintain temperature control, but you'll get better flavor.

Charcoal belches flamboyant white smoke when it is igniting. You don't want to add meat until the coals are fully aflame and at their peak in heat, when it has a white coat of ash. Then add wood at the start of the cook. Remember, charcoal is for heat, not flavor. If the temp runs up a bit at the start of the cook, it's not a big problem. The meat is cold and it can take a little extra heat. Then, when the wood burns out, stabilize the temp.

Keep your cooker clean. Sticky grease on your cooking grates can create black smoke and drip on the food. Grease smoke is not good smoke. Click here for more on cleaning your cooking grates. The black stuff on the walls probably has a lot of condensed creosote in it. A thin layer of neutral carbon is harmless, but black sticky goo is not. Many competition pitmasters power wash after a cookoff. Click here for more on cooker cleaning and maintenance.

Control oxygen. Make sure coals have plenty of oxygen. If coals are choking for lack of oxygen, they burn incompletely and can coat your food with gray soot. If that happens, get the meat off, rinse it, adjust the fire and put it back on. Don't let your embers sit in ash which can smother them. Keep them on a grate above the bottom of the firebox. Knock ash off occasionally and if necessary, remove it.

Use dry wood. Wet wood makes bad smoke. It also cools the fire. Read my article on soaking wood. Some pitmasters will even put the wood on top of their smoker to drive off any remaining water.

Size matters. For long cooks, chunks of wood from golf ball to baseball size work best. For short cooks, like a steak, chicken, or fish, small chips and especially pellets work best because they produce more smoke in a short burst. Some remove the bark from their wood.

Build a small hot fire. You want to see flame. Fires burning in the 650 to 750°F range in the hot spots burn off the impurities that can becreated in an incomplete secondary combustion. That means that you need a lot of oxygen so you want your exhaust vent open all the way. The hot air rising through the chimney will draw in air through the intake vent. You will probably want it open wide or close to it. Low smoldering wood creates dirty smoke.

This is why high quality offset smokers, the ones that look like a big barrel on its side with a small barrel attached, are so popular with experienced pitmasters. But there is a big difference between the cheap offsets at the hardware stores and the serious pits made for competition teams and caterers. Cheapo Offset Smokers (COS) include Brinkmann Pitmaster, Brinkmann Smoke'N Pit Professional, Char-Broil Silver Smoker, Char-Broil American Gourmet, and especially the Char-Griller Smokin Pro. They are nothing but headaches. The doors don't fit properly so you can't control oxygen intake, the walls are thin so they don't retain heat, and they rust. Expensive Offset Pits (EOS) include Horizon, Jambo, Klose, Lang, Meadow Creek, Peoria, Pitmaker, and Yoder to name a few. They are superb cooking tools. The picture below is inside the firebox of Darren Warth's Jambo. His team, Iowa's Smokey D's, one of the winningest cooks on the circuit. Notice that most of it is glowing embers and a log almost burnt to embers, and there on top is a small block of hardwood for flavor. Go to our equipment reviews database for ratings and reviews.

This is also a problem with kamados and eggs. They are so well insulated and so efficient with the heat right below the meat that they typically burn small cool fires and smolder white smoke.

Start charcoal and logs on the side. Start your logs or charcoal on the side and add only hot embers. I use a chimney in a wheel barrow. Remember, when it is burning properly, charcoal doesn't produce much smoke.

Allow the fire to get rolling and allow the pit to warm up. Start the fire well before the food goes on. Warm the walls of the cooker.When a recipe says "preheat" your cooker, do it. Adjust your airflow and get the temp, fire, and smoke stabilized. Be aware of the weather. It is harder to get blue smoke in cold, rainy, or windy weather.

Cook indirect. If the meat drips on the fire, water can douse the embers and fat can burn and produce dirty smoke. These drippings can create flavor, especially for short fast cooks, but for long low and slow cooks, they can cause problems.

Use your senses. It's hard to see the color of the smoke at night, but the smell should be sweet, with meat and spice fragrances dominating. The smoke aromas should be faint and seductive, perhaps like vanilla, not like a bonfire smell.

Use good thermometers. Cooking is all about temperature control. You need good thermometers in your cooker and in your meat. Enter the digital age and get a digital thermometer.

Practice. Do dry runs without food until you can anticipate when more fuel is needed, how to adjust the airflow, and how to react when the smoke starts going bad.

White smoke for short cooks (and when you have a new Pope)

White smoke usually has a compounds from incomplete combustion and prolonged exposure to white smoke is not ideal, it can still make good food. If you are cooking hot and fast, white smoke is a good way to get some smoke flavor on the food in a hurry. White smoke is best for short cooks like burgers or steak.

The best way to create white smoke is to deliberately starve the wood of oxygen and make it smolder. Experiment with containers for the wood. Here you can see a foil packet with holes punched in it and a small aluminum loaf pan crimped to restrict airflow. For short cooks, like a steak, chicken, or fish, small chips and especially pellets work best because they produce more smoke in a short burst.

![]()

In recent years there have been a dozen new products brought on the market to hold wood and add white smoke to the cooker. I have played with a number of them, and the one that impresses me the most is this clever design, especially for use with gas grills. It is called Mo's Smoking Pouch.

It is a pouch of fine mesh stainless steel that holds wood chips or pellets. The airspaces in the mesh are small enough that they limit the amount of air that gets in so the wood smolders and never bursts into flame. It puts out plenty of white smoke, usually within a few minutes. Best of all, it smokes just by putting it on top of the cooking grate or you can stand it on edge and slip it between the grates and the back of your grill. You don't have to squeeze it in down by the burners although you can if you need to space on top of the grates. And it works. It holds enough wood for about 15 minutes for short cooks, but you need to refill it, or buy a second pouch, for long cooks like pork shoulder and brisket. Refilling can be tricky since the steel gets hot and stays hot for a while. If you have good gloves, no problem.

Creosote

Creosote is among the compounds in smoke and it is the Jekyll and Hyde of smoke cooking. On the Dr. Jekyll side, creosote contributes positively to the flavor and color of smoked foods and acts as a preservative, among the reasons that smoking meat was used for preservation before refrigeration. Dr. Blonder says "Creosote is always present in charcoal or wood smoke, and a few components of creosote (guaiacol, syringol, and phenols) are the largest contributors to smoke flavor. No creosote, and the meat might as well have been boiled." On the Mr. Hyde side, "If the balance of the hundreds of chemicals in creosote shifts, it can taste bitter rather than smoky."

Commercial creosote is produced by distilling tars from primarily beechwood or bituminous coal (not charcoal). Careful control of the combustion temperature, oxygen flow, and pressure produce a wide range of aromatic oils and tars. Creosote from coal tar is the black stuff used to preserve telephone poles and railroad ties. Coal tar creosote is classified as a possible carcinogen. Anybody who has a wood burning fireplace knows that creosote from logs can cling to chimneys, clog them, and even ignite, burning down the house.

These industrial chemicals give the creosote found in barbecue smoke a bad name. I am unable to find any research that implicates the small amounts of creosote in barbecue with health risks.

According to Blonder, "When you smoke low and slow at temperatures like 225°F, many smokers require you to control the fire by damping the oxygen supply which moves it below the ideal combustion zone, creating black smoke, soot, and more creosote. Unfortunately, this is often the case with kamado and egg smokers. The best smokers combust at a high temp to create the ideal flavor profile and direct a small fraction of the smoke across the meat.

To control creosote, practice good fire management techniques and practice, practice, practice.

Smoke and food

In a smoker or grill, after combustion, the smoke rises and flows from the burn area into the cooking area. Most goes right up the chimney and very little contacts the food. Blonder explains why: "Around every object is a stagnant halo of air called the boundary layer. Depending on airflow, surface roughness, and so on, the stagnant layer of air around a piece of meat might be a millimeter or two in thickness. When smoke particles approach the meat's surface, they follow that boundary layer around the food. Very few ever touch down. We've all cursed a form of this piece of physics while driving: Gnats follow the airstream over the windshields, while larger insects leave green sticky splats at the point of impact."

So using a spice rub not only adds flavor, but it helps break up the boundary layer.

To show the way smoke sticks to food, we did some experiments.

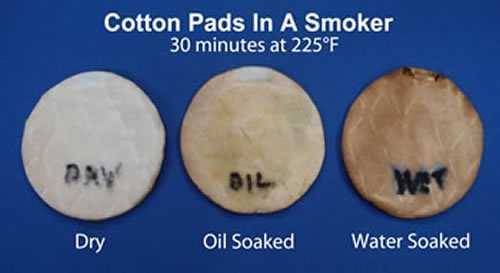

Blonder suspended three cotton disks in a smoker at 225°F for 30 minutes. One disk was dry, one soaked in oil, one soaked in water. The results were pretty dramatic. The atmosphere inside a smoker is as dense as a London fog, yet no visible smoke stuck to the dry cotton pad. Some smoke adhered to the oiled surface, and far more stuck to the wet surface.

Why does the wet pad gather so much more smoke? Blonder explains that smoke impacting the dry pad simply bounces off because there is nothing to hold it. But the oily and wet pads are tackier. But why does the wet pad attract more smoke than the oily pad? The answer is thermophoresis, according to the physicist.

Thermophoresis is a force that moves particles from a warm to a cold surface. Look at the three beer cans here. First we painted them white. The one on the left was filled with ice water and put in the smoker. The one in the middle was left empty and put in the smoker with the ice water can. The one on the right was left empty and sat on my desk as a control. You can see how much more smoke the cold can attracted. In fact you can even see where condensation on the can ran down the sides.

In the first experiment with cotton pads, in addition to the stickiness of water, the wet cotton pad was cooled by the evaporation of the moisture in the pad so it was well below the temp of the others. That's another reason why it was smokier.

The same thing happens to meat when you put it in the smoker. No matter what temperature your smoker's air is, the center of the meat, which is about 75% water, will never get hotter than 212°F, the boiling temp of water. It will start at about 38°F, refrigerator temp, and rise to perhaps 205°F. In theory the surface could dry out completely forming a very hard bark and it might get hotter than 212°F, but that is rarely the case. In fact, as the interior temp rises to about 200°F, it might even be hotter than the surface which is still being cooled by evaporation. So if you are cooking at 225°F or higher as I recommend, the meat will always be cooler than the air.

To see thermophoresis in action, do this experiment: Empty two beer cans the usual way. Fill one with ice cold water and leave the other empty. Put them in your smoker for 30 minutes. See which one is covered with smoke condensate.

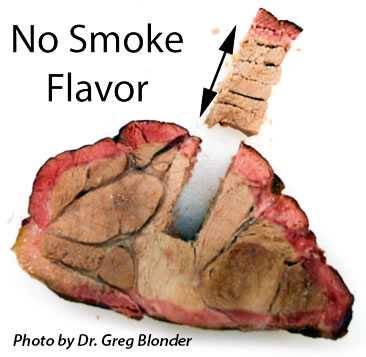

Smoke flavor is almost all on the surface of the food

As we see, smoke particles and gases glom onto the surface of foods. There they may dissolve and penetrate a tiny bit below the surface but not very far. Rarely more than 1/8". This is the same phenomenon with marinades. Meats, especially, are hard to penetrate. Don't believe me? Here's how to prove it to yourself. Get a four pound section of pork loin (not tenderloin). Cut it in half. Do not use rub, and smoke the heck out of one half at 225°F until it is about 180°F internal temp. Use as much smoke as you want. Bake the other half, sans rub, in the indoor oven at 225°F until it is about 180°F internal temp. Let them cool a bit and cut a slice out of the middle of each. Now take a core sample of each as in the picture below. Make sure the center meat doesn't get to roll around on the cutting board in the juices from the surface if there are any juices left in this lean cut. Have a friend serve the centermost parts to you with your eyes closed. No smoke!

Also, building enough smoke to create flavor takes time. On a thin skirt steak for fajitas, there will be much less smoke flavor than on a 1 1/2" thick ribeye steak cooked to medium rare, about 130°F. A thick steak will have much less smoke flavor than a chicken breast the same thickness because the chicken needs to be cooked longer, to 165°F. And a turkey breast will have more smoke flavor than all of them because it is thicker still.

Does meat stop taking on smoke?

There is a popular myth that at some point the meat stops taking on smoke. Sorry, but meat does not have doors that it shuts at some time during a cook. There is a lot of smoke moving through the cooking chamber although sometimes it is not very visible. If the surface is cold or wet, more of it sticks. Usually, late in the cook, the bark gets pretty warm and dry, and by then the coals are not producing a lot of smoke. Smoke bounces off warm dry surfaces so we are fooled into thinking the meat is somehow saturated with smoke. Throw on a log and baste the meat and it will start taking on smoke again. Just don't baste so often that you wash off the smoke and rub.

Less is more and enough is enough

One of the biggest mistakes we make is using too much smoke. Too much smoke can make your meat bitter or taste like an ash tray. I cannot give you a precise amount because each cooker is different and the amount of wood to get the right flavor will depend on the volume of the cooking chamber, the airflow, leaks, how often you peek, the kind of wood you use, basting, humidity, the weather, and of course, your preferences. You will need to experiment, but a good rule of thumb is start experimenting with about two ounces of wood, regardless of the cut or weight. For dense, thick cuts of meat such as pork butts for pulled pork or beef brisket, you can double or triple the amount of smoke. If the results are not smoky enough, you can add more wood on your next cook.

In any case, it is best to weigh the amount of wood you use so you can increase or decrease it as you wish in future cooks. Kitchen scales are very useful tools especially for flour and salts for curing. My favorite is the OXO Good Grips Stainless Food Scale with Pull-Out Display. It can weight accurately up to 11 pounds as well as fractions of an ounce. Push a button and it converts to metric. Put the bowl on the scale and push a button and it zeros out so the bowl's weight is not included. The top comes off for easy cleaning.

Here's where to start your experiments: On charcoal, start with no more than 8 ounces of wood by weight for pork and beef. Use no more than 4 ounces for turkey and chicken. Add it in doses. Put on about two ounces when you put on the meat and add another two ounces when you can no longer see smoke. On gas grills, double the amount because they have a lot of ventilation. Take notes. If you want more smoke after tasting the meat, add it 2 to 4 ounces at a time on subsequent cooks. Keep records of your experiments on a cooking log.

Unless your cooker is designed for it and unless you have a lot of experience, do not try to cook with wood for both heat and flavor. It is too hard to control the temp and the amount of smoke. When you become an expert, you may be able to cook with wood only, but at the outset stick to charcoal or gas. If you are ready to try, read this article on smoking with wood first.

Putting wood to work

So here's how to take advantage of this info.

Use cold meat. As described above, smoke is attracted to cold meat. Do not let the meat come to room temp. Besides, it takes forever for meat to come to room temp. Yet another myth.

Use a spice rub. Rough up the surface with a spice rub. A layer of spices and herbs helps to reduce the boundary layer so more smoke will stick.

Keep the meat moist. You can do this by spritzing the meat with a spray bottle you can buy in a drug store. A mop or basting brush can wash off your spice rub. You can use apple juice if you wish, but it adds very little to the flavor in comparison to the rub and sauce. You can use cranberry or pomegranate for color. But really, all you need is water. And don't worry, opening the cooker every 30 minutes to spritz will not slow the cooking process measurably. Yet another myth.

Add humidity to the atmosphere with a water pan in the smoker. And don't bother putting juice or beer in there. Use water pans in your smoker. They add water to the atmosphere, but more importantly the water slows evaporation keeping the meat's surface moist.

Add wood early but only after the fire is hot. Meat soaks up more wood flavor at the start of the cook, and the colder the meat the more smoke it absorbs. But don't put meat into a cooker with charcoal that is not fully engaged and belching smoke.

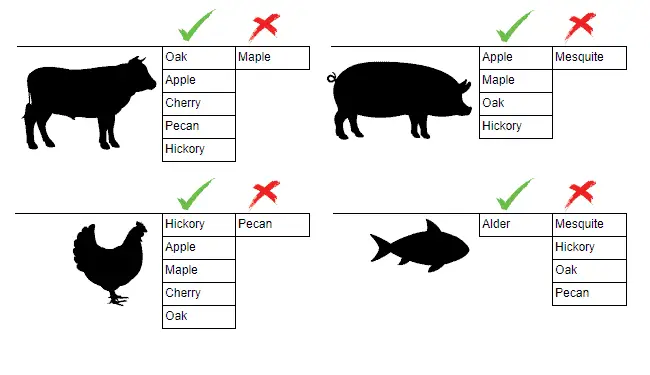

Which wood?

Cured (dried) hardwoods with low sap are the best for barbecue, especially fruit and nut woods. They all have slightly different flavors, and it is impossible to describe them. The internet is full of guides attempting to describe the flavors of different woods. They remind me of the florid descriptions wine lovers use. Most of them are just copied and pasted from website to website. I don't find these descriptions very useful. Frankly, I think most of it is a bunch of hooey. More barbecue mythology.

First of all, there are different kinds of each wood. For example, there's shagbark hickory, scrub hickory, pignut hickory, red hickory, and more. There's post oak, white oak, black oak, live oak, pin oak, and more. The climate the tree is grown in can impact flavor. Hot climate drought-stressed Texas oak grown in sand tastes different than cool climate Michigan oak grown in river silt. Furthermore, the amount of bark and can significantly impact flavor. How long it has dried and the percent water left in the wood significantly impacts flavor and aroma. And most importantly, the temperature of the fire, humidity of the cooker, and fuel type have a massive impact on flavor. Then throw your spice rub and sauce into the taste profile. Oh, I almost forgot, then there's the meat. Yakima Valley Washington Apple might taste one way on pork, but will taste entirely different on beef or turkey. Can you taste a smoked rib with Meathead's Memphis Dust and Sweet Baby Ray's sauce and tell me what wood was used? Get real.

To make matters worse, there is no guarantee that the wood in the bag is the wood on the label. Coffee, olive oil, and fish markets are regularly rocked by scandals of fraudulent labeling. How do we know that the bag of cherry wood sold in the big box hardware store is really cherry? When the warehouse for Home Depot calls and orders 10,000 bags of oak and the rickyard only has enough for 7,000 do you think that maybe they might mix in a little hickory to complete the order? You know they don't say "gosh we don't have it, why don't you call somebody else." Then there are pellets. Almost all wood pellets are at least half oak, with apple, cherry, etc. comprising the remainder. They do this to make it feed and burn more easily. What if you bought a tub of butter and it was really half margarine?

Here's the best I can do based on the woods I have used. I compiled this table from my notes and notes of others, but it is crucial that you understand that there are many many variables such as how dry the wood is and the species (there are at least 100 species of genus querkus, aka oak). Remember, I have judged food and wine around the world, I have won wine tasting championships in contests where I had to identify wines blind, and I would love nothing more than to tell you that a particular wood has "nuances of spice with an undertone of mushrooms". I just can't do it. There are too many variables.

| Genus | Smoke | Energy | Sparks | Embers |

| Alder | Mild | Low | Few | Fair |

| Apple | Medium | High | Few | Excellent |

| Cherry | Medium | Medium | Few | Excellent |

| Hickory | Strong | High | Few | Excellent |

| Maple | Mild | High | Few | Excellent |

| Mesquite | Strongest | High | Few | Excellent |

| Oaks | Medium | High | Few | Excellent |

| Peach | Medium | Medium | Few | Fair |

| Pear | Medium | High | Few | Fair |

| Pecan | Strong | High | Few | Good |

| Plum | Medium | High | Few | Excellent |

| Walnut | Strong | High | Few | Good |

I avoid mesquite although it is very popular in Texas. It can be harsh, bitter, and pungent. Hickory is the tried and true mate for pork, but some people find it too aggressive and occasionally it can taste bitter. Fruit woods tend to impart a sweetness, but this may just be the power of suggestion because we know fruit to be sweet. Then there are the exotic woods: Citrus, dried citrus peels, pistachio wood, corn cobs, nut shells, coconut shells, mango, and even mahogany. Who knows?

The choice of wood is crucial when you are using logs for both fuel for heat and for flavor. It is not very important when you are throwing a few chips and chunks into a pile of charcoal or onto a gas grill or even in a pellet smoker.

Stop obsessing over which wood to use. Pick one and stick with it for a while. The quality of the meat, the spice rub, fire control and cooking temp, the meat temp, and the sauce impact the final taste profile far more than the name on a bag of wood. Once you have everything else under control, then you can experiment with different woods.

Avoid softwoods. Whatever you do, never use wood from conifers such as pine, fir, cyprus, spruce, redwood, or cedar. They contain too much sap and turpenes, and they can make the meat taste funny. Some have been known to make people sick. Yes, I know that cedar planks are popular for cooking salmon on, but I don't know anyone who burns cedar as a smoke wood. I have also heard that elm, eucalyptus, sassafras, and sycamore impart a bad flavor. Many woods are can be irritants or poisonous, among them oleander, mangrove, laburnun, sassafras, tambootie, yew, and poisonous walnut (but not other walnuts). A good source for general info about woods is the wood database.

Never use lumber scraps. Some lumber is treated with chemicals that are poisonous. Never use wood that has been painted. By the way, that's one of the reasons I don't use lump charcoal. You can see lumber scraps in there and it makes me wonder how careful they are to prevent treated lumber from getting in the bag.

Never use wood that is moldy. Some molds contain toxins.

Use dry wood. Freshly cut "green" woods have more sap, burn irregularly, and impart different flavors than dried wood. Air dried wood is usually slightly wetter than kiln dried. Kiln dried used to be rare but with more and more restaurants using wood for grilling, kiln dried has become more common as health departments demand it to kill insects, molds, and bacteria. The wood is placed in a room and heated to 200 to 240°F to drive off the moisture. If you buy kiln dried, ask for 15 to 22% moisture. The water provides steam that makes the droplets larger and stickier.

Bark or no bark? Some wood has more bark than others and that can impact the flavor. Some folks say you should remove the bark. Bark has more air in it and is less tightly bound so it will burn differently than heartwood. I don't remove it, but I try to keep it to a minimum. I know top cooks who remove it all. I know one cook who says hickory bark is the only one good enough to use.

What do I prefer? If I was on a dessert island I would want a bag of apple chunks and a bag of small apple chips or pellets. I would use the chunks for steady slow release smoke, and the chips or pellets for quick smoke. Apple is mild and rarely tries to take center stage.

Where to get it? There are a number of barbecue specialty stores opening around the country and there may be one near you. Most hardware stores carry only hickory or mesquite, but a few carry expanded barbecue supplies and a selection of woods. Watch the newspaper for ads from stores promoting a lot of grills. Then give them a call. Another option is to go to an orchard and ask if you can have some dead trees or limbs but be careful, they could be laden with pesticides or other sprays. Also there are a number of places to buy wood on the net. Click here for contact info for online wood suppliers.

The different shapes of wood

Logs. Most barbecue woods are cut from hardwoods, fruitwoods, and nutwoods, but never pine and softwoods that have a lot of turpenes and sap. Logs must be dried. Here is a small part of the acre sized pile of post oak at Kreuz Market in Lockhart. TX.

Logs. Most barbecue woods are cut from hardwoods, fruitwoods, and nutwoods, but never pine and softwoods that have a lot of turpenes and sap. Logs must be dried. Here is a small part of the acre sized pile of post oak at Kreuz Market in Lockhart. TX.

Some cooks throw whole logs into their pits, but you must have the right pit and skill set to pull this off. Done improperly this can easily ruin your meat.

More commonly, "stick burners" preburn the logs reducing them to embers before cooking with them. Smoking with logs usually needs to be done at a higher temp, perhaps 275°F rather than 225°F because the fire must be hot in order to create clean smoke. Click here for more on cooking with logs.

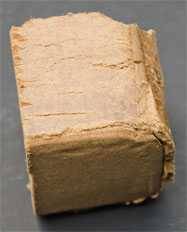

Squogs. In 2018 Ole Hickory Pits introduced Squogs, hickory logs that have been milled square like lumber into uniform 3.5 x 3.5 x 12" blocks. They are designed for stick burning pits like the ones they manufacture. They have some real advantages. There is no bark so they are consistent quality, they stack neatly on pallets, and bark is often dirty, flakes off, and hides bugs. Very clever.

Chunks. Wood chunks from golf ball to fist size are fairly easy to find in hardware stores. Chunks burn more slowly that chips, and often a chunk or two about the size of an egg weighing 2 to 4 ounces is all that is necessary for a load of food. Because they are slow, steady sources of smoke, they are in many ways, the most desirable. When you use chunks, you can add one or two at the start of the cooking cycle and you don't need to keep opening the unit and mess with the equilibrium in the cooking chamber's atmosphere.

Chips. About the size of coins, chips are also common and easy to find. They burn quickly and you may find that you need to add them more than once during the cooking cycle. Chips are fine for short cooks, but for long cooks, chunks are better.

Pellets. Pellets are made by compressing wet sawdust and extruding it in long pencil thick rods. They are broken into small bits about 1/2" long. Food grade pellets contain no binders, glue or adhesives, and when they get wet they revert to sawdust immediately. Some smokers use pellets as the main fuel, for both flavor and heat and pellet cookers do very very well in competition. Because they can be fed into the fire in a very controlled manner, usually by an auger, pellet cookers can be regulated with a thermostat, making them very controllable. They burn very hot and clean.

Food grade pellets can be a good source of smoke flavor on grills and smokers for short cooks, and a handful or two is usually all that is necessary for poultry.

Pellets used as fuel to fire pellet grills are mostly oak, a stable burning wood. If they say they are hickory, they are usually less than half hickory, a fact that does not always appear on the label. They usually come in 10 to 40 pound bags.

BBQr's Delight makes a dozen flavors of pellets in small 1/10 pound or 1 pound bags that are 100% flavor wood including alder, apple, cherry, hickory, orange, pecan, and others. Their Jack Daniel's pellets are a mix of oak and charcoal from oak whiskey barrels, and their Savory Herb is oak with herbs in the blend. I love using these products because they are easy to measure and control. They only burn for about 20 minutes at 225°F, so you must get your meat on before the wood.

Click here to learn more about pellet smokers, how they work, and get a link to our reviews of more than a dozen of these new devices..

Bricks. Another form of pellet is the brick, the most notable being made by Mojo-Bricks (right). These are wood chips and sawdust from the mills compressed until they bind. They come in a number of flavors. I have had very good luck with them on a variety of smokers.

Bisquettes. Bisquettes are another variation on the compressed sawdust idea made for the Bradley Smoker. They look like small brown hockey pucks.

Sawdust. Sawdust can also be used for flavor, but it burns quickly and is rarely used. There are even a few small smokers, like the Camerons, that use smoldering sawdust. It can be used effectively on thin, fast cooking foods like fish filets.

For gas grills

Getting smoke on gas grills is sometimes tricky. You need to experiment. On your grill you may prefer the flavor of smoldering chunks or fast burning chips. Taste is a matter of taste. Here are some things to try.

Get a charcoal assist. Sometimes wood just won't burn. A reader, Nei Ng, found a solution: "The first thing to do is to wrap the wood in foil like the wood chip pouches. Make a small pile of charcoal on the flavor bars [or heat dispersers]. They will ignite, but the pile isn't hot enough to really change the overall temperature, and the wood should be lit by the time the grill has reached 225°F. Place the wood over the hot charcoal and it should start smoking within a few minutes."

The foil pouch for chips. Put wood chips in a foil pouch or make a smoke bomb (elsewhere on this page). For a pouch, use heavy duty foil or two or three layers or regular foil. Poke holes in the top so the smoke can escape. Place the pouch as close to the heat as possible. Reader Jeff Hale has this tip: "Make up a bunch of pouches in advance. When one is burnt up... throw another one on." You will know when to add a new pouch when the smoke stops. Another option is to use a small aluminum pan with holes poked in the bottom.

If you are having problems getting the wood in a pouch to smoke, before you put the meat on, turn the burner on high, put the foil packet on and wait for the chips to begin smoking. Then dial the burner down so you can get the oven to 225°F. Or try Nei Ng's technique of using charcoal (above).

Try putting the wood in a small cast-iron frying pan or a flattened steel can.

If the wood burns. It is possible that your wood might just catch on fire and not smoulder. Don't worry! Remember, small hot fires prooduce the best tasting smoke. You will use more wood than if you let it smolder, but you may just like the flavor better.

Smoking indoors with sawdust

If you have a good exhaust system smoking with sawdust works well. If you have a wimpy fan, don't even think about it.

The best source of sawdust is to take a handful of wood pellets, get them wet, and either let them air dry or pan dry them on a low temp. You can get quality hardwood sawdust from a local cabinet maker or lumber yard, but often it is mixed with pine and other woods.

Get a stainless roasting pan, cover the bottom with heavy duty foil. Sprinkle sawdust on top and place a layer of foil over it, but not all the way to the edge. This keeps drippings from extinguishing the smoldering wood and allows the smoke to escape around the edges. Place a rack like a pie cooling rack above the sawdust sandwich. The food goes on the rack, and then cover the whole shootin' match. You can make a cover several ways.

- Lay a second, identical roasting pan upside down on top, and clamp it down with metal or wooden clothes pins.

- Lay a sheet pan on top of the roasting pan and weight it down with a sauce pan or a brick.

- You can fashion a lid from foil, just crimp it tight around the edges. Foil is a good method if you need to insert a food thermometer or if the food is tall.

Place the whole shooting match on top of the burners on the stove and crank up the exhaust. When the smoke stops, you can check the meat temp. If it is not done, pop it into the oven at about 325°F.

Meathead's smoke bombs

This method is ideal for both gas and charcoal cookers when you have a long cook and getting under the grate will be tricky, like when there's a full packer brisket on board.

This method is ideal for both gas and charcoal cookers when you have a long cook and getting under the grate will be tricky, like when there's a full packer brisket on board.

Get two disposable aluminum loaf pans. Add dry wood to both. Pour enough water in one to cover the wood. The dry pan will start to smoke quickly. About 15 minutes after it is all consumed, the other pan will have dried out and begun smoking.

Getting the correct amounts of wood and water may take you a few cooks to perfect, but you will figure it out. I can tell that much about you.

Smoking with herbs

We have a nice herb garden and at the end of the season there are always a few unpicked oregano, basil, and other herb bushes. I cut them above the roots, and stick them in paper bags to dry. Then I crumble them, and I throw them on the grill after the meat is on. They burn fast, put out a lot of smoke that smells like you are doing something illegal, and add an exotic aroma to the food. I use them mostly on my gas grill on seafood, which cooks quickly and doesn't have time to absorb slowly smoldering hardwood.

Tea smoking

Chinese cooking often calls for tea smoking. Make a foil packet of these ingredients and place it under the meat.

1/4 cup tea leaves

1/4 cup brown sugar

1/4 cup rice

zest of 1 orange

6 whole star anise pods

2 (3" long) cinnamon sticks

1 tablespoon powdered ginger

Bottom line

Sterling Ball is a champion pitmaster whose trophies include the Kansas City Royal Invitational also owns a guitar string business. He describes the art of making tasty smoke as similar to tuning a guitar. "You need control of your instruments, the pit, fuel, oxygen, fire, and heat. And you need to practice."

[mailerlite_form form_id=1]

To me, barbecue is not a cuisine, it’s an event and I’ll explain that to you and I’ll explain what that means. So many people that I’ve run across always talk about recipes or they show recipes and to me, I’ve developed recipes, I’ve been cooking for a very long time, and it’s not about the recipe, it’s about the event. It’s about when you’re outside doing a barbecue, what is the emotion that’s being created? What are the bonds that are being created? What are the memories that keep coming back from previous barbecues? That’s what barbecue is.

To me, barbecue is not a cuisine, it’s an event and I’ll explain that to you and I’ll explain what that means. So many people that I’ve run across always talk about recipes or they show recipes and to me, I’ve developed recipes, I’ve been cooking for a very long time, and it’s not about the recipe, it’s about the event. It’s about when you’re outside doing a barbecue, what is the emotion that’s being created? What are the bonds that are being created? What are the memories that keep coming back from previous barbecues? That’s what barbecue is.

omewhere around the Fourth of July, something that meant to people as a whole and to America, and about the third trip when I got there, a general actually and an officer of the clergy came up to me and said, “Hey Pat, these barbecues are helping and ministering to these kids far beyond what you realize”? They said for months and months afterward, they still talk about them.

omewhere around the Fourth of July, something that meant to people as a whole and to America, and about the third trip when I got there, a general actually and an officer of the clergy came up to me and said, “Hey Pat, these barbecues are helping and ministering to these kids far beyond what you realize”? They said for months and months afterward, they still talk about them.